In time to come, advocates of accessibility in games may see the hope of well and truly demolishing another barrier realised. When that happens, Naughty Dog’s remake of The Last of Us Part 1 will no longer be the sole game to have audio descriptions for cutscenes, and it will be bested by games that go further. The Last of Part 1’s remake will merely be the game that started it all — and Descriptive Video Works (DVW), the service-provider who partnered with Naughty Dog to create the remake’s audio descriptions, is working towards making that a reality.

For those unfamiliar with DVW’s work in games media, its involvement goes back to 2018, with Netflix’s acquisition of the now-retired Minecraft: Story Mode. It ramps up in 2020 after helping with Ubisoft’s game trailers and providing its live description service for The Game Awards. And according to Rhys Lloyd, DVW’s studio head, it’s been actively pushing for games to have integrated audio descriptions as part of progress for vision accessibility for players since.

While DVW were advocates, the chance to work on a game didn’t come along until Brandon Cole, a blind accessibility consultant who works on DVW’s advisory board, found himself involved in Naughty Dog’s pursuit of accessibility. Suddenly, DVW was brought on board.

“When we first got the call to do The Last of Us Part 1 it was very exciting and somewhat daunting to be moving from having advocated for the inclusion of audio description in videogaming to actually producing the first ever AD track for a triple-A game,” Lloyd says.

But audio description isn’t as simple as just describing what you see on a screen. Production took months, and at every step of the way — from finding the right staff writer, to drafting a script, to hiring a narrator who could have a firm grasp of the content, to delivery — DVW worked closely with Naughty Dog to ensure the depth and feel of the world in cutscenes of The Last of Us were properly communicated to players.

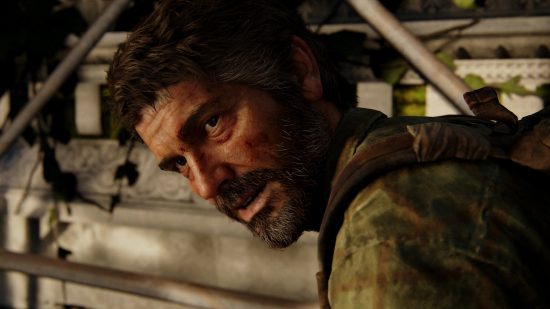

There was also the issue of what form the first attempt at audio descriptions in games would take. How much should be narrated? How far could they go? The finished product DVW and Naughty Dog crafted on uncharted waters would ultimately earn them widespread praise, but there was one aspect blind and low-vision gamers singled out as disappointing in their critiques of the remake and its accessibility: the lack of descriptions for scenes that take place within gameplay and for the various abandoned, barely-surviving, and occasionally verdant settings Joel and Ellie would find themselves in.

“That was an intentional decision,” Lloyd says. A specific and explicit one by both studios, as a workable entry point to adapting the typical processes for creating audio descriptions to game development. The high level of engagement with its newest client in the industry was a considerable shift of its role in the pipeline for DVW; the studio was usually one of the last to work on projects before distribution, not in the trenches of actively developing a project with its creators.

Partnering with games studios is, as Lloyd puts it, “a marathon more than a sprint.” One that leaves interesting lessons, such as the number of iterations a draft can go through before it’s finalised.

“Would we like to go further in the future iterations of audio description in gaming? Absolutely,” Lloyd says, in response to blind and low-vision gamers taking note of where DVW’s work could’ve been improved in The Last of Us Part 1 remake. “We are already seeing that happen.”

DVW didn’t disclose which games studios it’s speaking with, but Lloyd says he’s had conversations with studios about providing service and are already in the early stages of development with some. A new challenge that’s cropped up, which was largely avoided with The Last of Us Part 1 remake, though, is that of continuity.

Unlike with the remake and other types of media, stories being built from scratch in gaming are pieced together and iterated upon in bits and chunks, at times leaving DVW with months-long gaps between project responsibilities. But according to Lloyd, DVW is adapting as always, with an attitude of approaching every project as a clean slate.

The team believes gamers will see an increased prevalence of audio descriptions in games, showcases, and events in the coming months. DVW’s optimism is backed by plans to expand its service. In addition to the narration of gameplay elements being on the table, DVW is rolling out support for ten more languages throughout 2023 to meet international need and demand. It’s also diversifying its roster of voice talent to better serve marginalised communities.

“Ensuring that the content is narrated by people who can form a connection to the subject matter elevates the audio description to a new level,” Lloyd says. “We’ve spoken to members of the blind and low vision community, and [they’ve] highlighted that it’s important for people who are watching a show to know that the content was worked on by people who share some of those lived experiences, that we aren’t making assumptions, and that we’re trying to meet the content where it is.”

When asked about what DVW and Lloyd himself hopes for games accessibility for the near future, Lloyd was enthusiastic in offering a picture where audiences are responding to accessibility as a creative endeavor within games in and of itself, instead of the so-called novelty of its existence in the present. “I look forward to a time when we can discuss the creative choices that were made in describing a game, and not simply the fact it exists,” he says. He also looks forward to give audiences the ability to customise audio description systems and content to their personal preference.

But what he’s most looking forward to is the fact that audio description as a service, Lloyd says, “has the opportunity to get a rebirth with interactive media and we’re really excited to be a part of that.”